SleepGuard

Photo by Alexandra Gorn on Unsplash

Photo by Alexandra Gorn on Unsplash

This is a side project I developed in phase II of the MIT-Catalyst program, which I was part of in cohort 2023.

Disturbed sleep is a core symptom of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), significantly impacting overall health, quality of life, and the effectiveness of treatments. Despite its critical role, addressing sleep issues in PTSD patients has been a challenging endeavor. This is largely due to the reliance on self-assessments, which are often unreliable and subjective. Consequently, treatment choices can become more of a gamble than an informed decision. To bridge this gap, there is a pressing need for objective sleep data that can provide a more solid foundation for targeted treatment choices. This is where our project comes into play. Laura Bajor, Enrique Gutiérrez (Kike) and myself aim to leverage sleep data from wearable devices to inform patient-provider collaboration and guide treatment decisions.

In this project, Laura Bajor, Enrique Gutiérrez and myself want to significantly improve the treatment of PTSD-related sleep problems by creating a Collaboration Support Tool that processes and delivers sleep data from wearable devices and delivers it to patients and providers in a format that facilitates improved collaboration and outcomes. Our intent is to create a system with the potential to improve quality of life for millions of Americans living with PTSD, to prevent the onset of associated chronic conditions and to preserve valuable resources on a systems-level.

Why is this an important need worth addressing?

Numbers speak for themselves: around 13 million Americans suffer from PTSD, with 90% reporting sleep disturbances. Veterans are particularly at risk; research indicates that of the 6 million veterans who served in the 2021 fiscal year, about 10% of men and 19% of women were diagnosed with PTSD. Left untreated, sleep disturbances can exacerbate symptoms, contribute to additional health issues, relationship problems, and higher risk for developing substance use disorder. So, yes, it is a big deal.

The problem with self-assessments and the need for objective data

Self-assessments are commonly used in clinical settings to gauge the severity of sleep disturbances in PTSD patients. However, these assessments are fraught with inaccuracies. Patients may underreport or overreport their symptoms due to various factors such as memory bias, emotional state, or misunderstanding of their own sleep patterns. Imagine yourself after a poor-sleep night: would you be able to say whether you were just unable to get asleep, or whether you woke up multiple times during the night? Or, you may feel like you slept for 3 hours when in reality you slept for 6 (though with poor quality). This lack of reliable data complicates the treatment process, making it difficult for providers to tailor interventions effectively.

Objective sleep data can offer a more accurate and comprehensive picture of a patient’s sleep patterns. This data can be instrumental in diagnosing the severity of sleep disturbances and in monitoring the effectiveness of treatments. By providing a solid foundation of reliable information, objective data can help in making more informed treatment decisions, thereby improving patient outcomes.

Leveraging wearable technology and AI

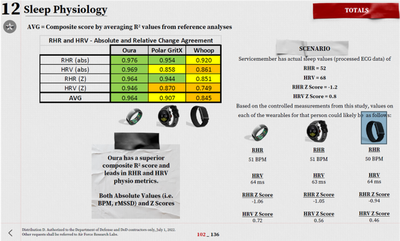

Wearable devices have revolutionized the way we monitor health metrics, including sleep. These devices can track various parameters such as sleep duration, sleep stages, heart rate, and movement. By collecting and analyzing this data, we can gain valuable insights into a patient’s sleep patterns, which can then be used to guide treatment decisions. In particular, it has been found that the Oura ring is the most promising device for this task.

The Oura ring is a wearable device that tracks sleep patterns, heart rate, and activity levels. It provides detailed insights into sleep quality, including metrics like total sleep time, sleep efficiency, time spent in different sleep stages (light, deep, REM), and any disruptions during the night.

By collecting and modelling this data, we may be able to identify patterns and anomalies associated with sleep disturbances, as well as predict relevant significant outcomes or response to treatment. This information can then be used to guide treatment decisions, such as adjusting medication dosages, introducing new interventions, or modifying existing therapies.

What are we doing to address this unmet need?

Our long-term goal is to develop an integrated system using data from wearable devices to analyze and model sleep data in a clinical decision support (CDS) system that supports patients and providers in collaboration toward relief of PTSD symptoms. For this purpose, we initially need to integrate the Oura ring data into a system that can process and deliver this information in a useful format to patients and providers. Here’s how the process works:

- Subject matter experts (SME) survey: We conducted a survey with clinicians (43 responses) to understand their confidence in using wearable data and their treatment choices based on this data. The results showed that clinicians have moderate to high confidence in the accuracy and usefulness of wearable data. They are willing to use a system that is cohesive and time-neutral, and that provides recommendations on the use of this data.

-

Data collection: Pulling sleep data from the Oura API into a secure MIT server (currently through the MIT dropbox account). This data is collected from patients wearing the Oura ring (at the moment, tests are done on fellows' data, NOT real patients). Python code is used to pull/ sort wearable data.

-

Dashboard design: The useful metrics agreed to by the SME are displayed in a preliminary dashboard design. This design will be further refined based on feedback from clinicians and patients. The dashboard will be designed to be user-friendly and intuitive, providing a clear overview of the patient’s sleep patterns and any anomalies detected.

-

Patient-provider collaboration: The analyzed data is shared with both the patient and the provider. This information serves as a basis for discussions about the patient’s sleep issues and potential treatment options. By involving the patient in the decision-making process, we aim to foster a collaborative approach to treatment that empowers the patient to take an active role in managing their sleep disturbances.

-

Guiding treatment decisions: Based on the objective data, providers can make more informed decisions about treatment strategies. This may include adjustments to existing treatments or the introduction of new interventions specifically targeted at improving sleep quality.

-

Monitoring and adjustments: The wearable continues to collect data throughout the treatment process. This ongoing monitoring allows for real-time adjustments to the treatment plan, ensuring that it remains effective over time.

Currently, we are collaborating with different entities, including the VA Office of Connected Care “Patient Generated Health Data” Team, the Oura Corporation’s Government/Military Division, and the US Air Force Research Lab Human Performance Division and Special Operations Command Human Performance Divisions. We are also in contact with the VA Tech Transfer office for funding applications.

My role in this project revolved around ideation and the technical implementation: building a pipeline to get input data from Oura API, cleaning, processing and building a prototype dashboard together with Kike. I’m extremely excited about the process of creating a tool from scratch, and one that can improve the lives of so many people!

** March 2024 follow-up on the project **

-

The VA Office of Connected Care received very well this project, and there is interest in incorporating it on their already existing set of PowerBI dashboards. Co-creation of the dashboard for implementation in Proof of Concept Study is to be done in the next months.

-

There is a longer term goal of liaising with Dr. Mikhail Kuprian at VA OCC and Dr. Laura Lewis at MIT on use of a large data set for ML/AI purposes, to study the relationship between medication changes and sleep data.

-

As for the medical implementation, a partnership with the VA Office of Connected Care “Patient Generated Health Data” Team has been established. IRB approved for a small in vivo trial (N=20). The goals of this “in vivo feasibility study” are 1) demonstrating the usability of devices in a clinical setting, 2) assessing the impact of patients having access to their own data on patient/provider interaction, and 3) addressing “system glitches” prior to a wider-scale Proof of Concept study.

-

My contribution to this project is currently on hold, as the data analytics and modelling part is not needed at this stage. However, I am excited about the project’s potential and, as a Catalyst fellow, I look forward to possibly rejoining at a later stage where my skills and experience can add significant value.